Windows users

- Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL2). Ubuntu version recommended, then follow Ubuntu-specific instructions.

- Virtual machine (such as VirtualBox).

- (Expert users) Dual boot.

macOS users

Linux users

- Install Python 3 and GCC using your package manager (such as apt, yum, pacman).

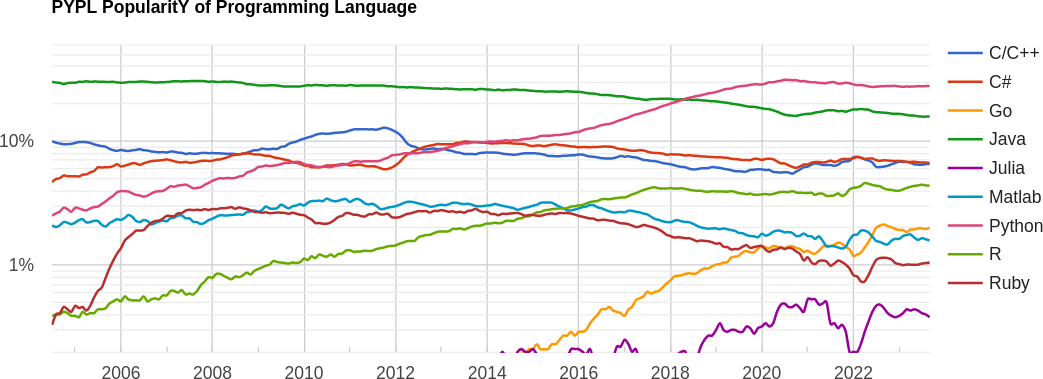

Popularity of programming languages

Source: https://pypl.github.io/PYPL.html

Curated lists of awesome C++ and Python frameworks, libraries, resources, and shiny things.

Outline

- The build process:

- Compiled vs. interpreted languages.

- Preprocessor, compiler, linker, loader.

- Introduction to the UNIX shell:

- What is a shell.

- Variables.

- Basic commands and scripting.

- Introduction to

git:- Local vs. remote.

- Branching and collaborative working.

- Sync the course material with your computer.

- Exercises.

The build process:

Preprocessor, Compiler, Linker, Loader

Compiled vs. interpreted languages

The build process

Preprocessor

- Handles directives and macros before compilation.

- Originated for code reusability and organization.

Preprocessor directives

#include: Includes header files.#define: Defines macros for code replacement.#ifdef,#ifndef,#else,#endif: Conditional compilation.#pragma: Compiler-specific directives.

Macros

- Example:

#define SQUARE(x) ((x) * (x)) - Usage:

int result = SQUARE(5); // Expands to: ((5) * (5))

Compiler

- Translates source code into assembly/machine code.

- Evolved with programming languages and instructions.

Compilation process

- Lexical analysis: Tokenization.

- Syntax analysis (parsing): Syntax tree.

- Semantic analysis: Checking.

- Code generation: Assembly/machine code.

- Optimization: Efficiency improvement.

- Output: Object files.

Common compiler options

-O: Optimization levels; -g: Debugging info; -std: C++ standard.

Linker

- Combines object files into an executable.

- Supports modular code.

Linking process

- Symbol resolution: Match symbols.

- Relocation: Adjust addresses.

- Output: Executable.

- Linker errors/warnings.

- Example:

g++ main.o helper.o -o my_program

Static vs. dynamic linking

- Static: Larger binary, library inclusion.

- Dynamic: Smaller binary, runtime library reference.

Loader

- Loads executables for execution.

- Tied to memory management evolution.

Loading process

- Memory allocation: Reserve memory.

- Relocation: Adjust addresses.

- Initialization: Set up environment.

- Execution: Start execution.

Dynamic linking at runtime

- Inclusion of external libraries during execution.

- Enhances flexibility.

Introduction to the UNIX shell

What is a shell?

From http://www.linfo.org/shell.html:

A shell is a program that provides the traditional, text-only user interface for Linux and other UNIX-like operating systems. Its primary function is to read commands that are typed into a console [...] and then execute (i.e., run) them. The term shell derives its name from the fact that it is an outer layer of an operating system. A shell is an interface between the user and the internal parts of the OS (at the very core of which is the kernel).

What is Bash?

Bash stands for: Bourne Again Shell, a homage to its creator Stephen Bourne. It is the default shell for most UNIX systems and Linux distributions. It is both a command interpreter and a scripting language. The shell might be changed by simply typing its name and even the default shell might be changed for all sessions.

macOS has replaced it with zsh, which is mostly compatible with Bash, since v10.15 Catalina.

Other shells available: tsh, ksh, csh, Dash, Fish, Windows PowerShell, ...

Variables and environmental variables

As shell is a program, it has its variables. You can assign a value to a variable with the equal sign (no spaces!), for instance type A=1. You can then retrieve its value using the dollar sign and curly braces, for instance to display it the user may type echo ${A}. Some variables can affect the way running processes will behave on a computer, these are called environmental variables. For this reason, some variables are set by default, for instance to display the user home directory type echo ${HOME}. To set an environmental variable just prepend export, for instance export PATH="/usr/sbin:$PATH" adds the folder /usr/sbin to the PATH environment variable. PATH specifies a set of directories where executable programs are located.

Types of shell (login vs. non-login)

- A login shell logs you into the system as a specific user (it requires username and password). When you hit

Ctrl+Alt+F1to login into a virtual terminal you get after successful login: a login shell (that is interactive). - A non-login shell is executed without logging in (it requires a current logged in user). When you open a graphic terminal it is a non-login (interactive) shell.

Types of shell (interactive vs. non-interactive)

- In an interactive shell (login or non-login) you can interactively type or interrupt commands. For example a graphic terminal (non-login) or a virtual terminal (login). In an interactive shell the prompt variable must be set (

$PS1). - A non-interactive shell is usually run from an automated process. Input and output are not exposed (unless explicitly handled by the calling process). This is normally a non-login shell, because the calling user has logged in already. A shell running a script is always a non-interactive shell (but the script can emulate an interactive shell by prompting the user to input values).

Bash as a command line interpreter

When launching a terminal a UNIX system first launches the shell interpreter specified in the SHELL environment variable. If SHELL is unset it uses the system default.

After having sourced the initialization files, the interpreter shows the prompt (defined by the environment variable $PS1).

Initialization files are hidden files stored in the user's home directory, executed as soon as an interactive shell is run.

Initialization files

Initialization files in a shell are scripts or configuration files that are executed or sourced when the shell starts. These files are used to set up the shell environment, customize its behavior, and define various settings that affect how the shell operates.

-

login:

/etc/profile,/etc/profile.d/*,~/.profilefor Bourne-compatible shells~/.bash_profile(or~/.bash_login) forBash/etc/zprofile,~/.zprofileforzsh/etc/csh.login,~/.loginforcsh

-

non-login:

/etc/bash.bashrc,~/.bashrcforBash

Initialization files

-

interactive:

/etc/profile,/etc/profile.d/*and~/.profile/etc/bash.bashrc,~/.bashrcforBash

-

non-interactive:

/etc/bash.bashrcforBash(but most of the times the script begins with:[ -z "$PS1" ] && return, i.e. don't do anything if it's a non-interactive shell).- depending on the shell, the file specified in

$ENV(or$BASH_ENV) might be read.

Getting started

To get a little hang of the bash, let’s try a few simple commands:

echo: prints whatever you type at the shell prompt.date: displays the current time and date.clear: clean the terminal.

Basic Bash commands

pwdstands for Print working directory and it points to the current working directory, that is, the directory that the shell is currently looking at. It’s also the default place where the shell commands will look for data files.lsstands for a List and it lists the contents of a directory. ls usually starts out looking at our home directory. This means if we print ls by itself, it will always print the contents of the current directory.cdstands for Change directory and changes the active directory to the path specified.

Basic Bash commands

cpstands for Copy and it moves one or more files or directories from one place to another. We need to specify what we want to move, i.e., the source and where we want to move them, i.e., the destination.mvstands for Move and it moves one or more files or directories from one place to another. We need to specify what we want to move, i.e., the source and where we want to move them, i.e., the destination.touchcommand is used to create new, empty files. It is also used to change the timestamps on existing files and directories.mkdirstands for Make directory and is used to make a new directory or a folder.rmstands for Remove and it removes files or directories. By default, it does not remove directories, unless you provide the flagrm -r(-rmeans recursively).Warning: Files removed via

rmare lost forever, please be careful!

Not all commands are equals

When executing a command, like ls a subprocess is created. A subprocess inherits all the environment variables from the parent process, executes the command and returns the control to the calling process.

A subprocess cannot change the state of the calling process.

The command source script_file executes the commands contained in script_file as if they were typed directly on the terminal. It is only used on scripts that have to change some environmental variables or define aliases or function. Typing . script_file does the same.

If the environment should not be altered, use ./script_file, instead.

Run a script

To run your brand new script you may need to change the access permissions of the file. To make a file executable run

chmod +x script_file

Finally, remember that the first line of the script (the so-called shebang) tells the shell which interpreter to use while executing the file. So, for example, if your script starts with #!/bin/bash it will be run by Bash, if is starts with #!/usr/bin/env python it will be run by Python.

Built-in commands

Some commands, like cd are executed directly by the shell, without creating a subprocess.

Indeed it would be impossible the have cd as a regular command!

The reason is: a subprocess cannot change the state of the calling process, whereas cd needs to change the value of the environmental variable PWD(that contains the name of the current working directory).

Other commands

In general a command can refer to:

- A builtin command.

- An executable.

- A function.

The shell looks for executables with a given name within directories specified in the environment variable PATH, whereas aliases and functions are usually sourced by the .bashrc file (or equivalent).

- To check what

command_nameis:type command_name. - To check its location:

which command_name.

A warning about filenames

Space characters in file names should be forbidden by law! The space is used as separation character, having it in a file name makes things a lot more complicated in any script (not just Bash scripts).

Use underscores (snake case): my_wonderful_file_name, or uppercase characters (camel case): myWonderfulFileName, or hyphens: my-wonderful-file-name, or a mixture:

myWonderful_file-name, instead.

But not my wonderful file name. It is not wonderful at all if it has to be parsed in a script.

More commands

catstands for Concatenate and it reads a file and outputs its content. It can read any number of files, and hence the name concatenate.wcis short for Word count. It reads a list of files and generates one or more of the following statistics: newline count, word count, and byte count.grepstands for Global regular expression print. It searches for lines with a given string or looks for a pattern in a given input stream.headshows the first line(s) of a file.tailshows the last line(s) of a file.filereads the files specified and performs a series of tests in attempt to classify them by type.

Redirection, pipelines and filters

We can add operators between commands in order to chain them together.

- The pipe operator

|, forwards the output of one command to another. E.g.,cat /etc/passwd | grep my_usernamechecks system information about "my_username". - The redirect operator

>sends the standard output of one command to a file. E.g.,ls > files-in-this-folder.txtsaves a file with the list of files. - The append operator

>>appends the output of one command to a file. - The operator

&>sends the standard output and the standard error to file. &&pipe is activated only if the return status of the first command is 0. It is used to chain commands together: e.g.,sudo apt update && sudo apt upgrade||pipe is activated only if the return status of first command is different from 0.;is a way to execute to commands regardless of the output status.$?is a variable containing the output status of the last command.

Advanced commands

trstands for translate. It supports a range of transformations including uppercase to lowercase, squeezing repeating characters, deleting specific characters, and basic find and replace. For instance:echo "Welcome to Advanced Programming!" | tr [a-z] [A-Z]converts all characters to upper case.echo -e "A;B;c\n1,2;1,4;1,8" | tr "," "." | tr ";" ","replaces commas with dots and semi-colons with commas.echo "My ID is 73535" | tr -d [:digit:]deletes all the digits from the string.

Advanced commands

sedstands for stream editor and it can perform lots of functions on file like searching, find and replace, insertion or deletion. We give just an hint of its true powerecho "UNIX is great OS. UNIX is open source." | sed "s/UNIX/Linux/"replaces the first occurrence of "UNIX" with "Linux".echo "UNIX is great OS. UNIX is open source." | sed "s/UNIX/Linux/2"replaces the second occurrence of "UNIX" with "Linux".echo "UNIX is great OS. UNIX is open source." | sed "s/UNIX/Linux/g"replaces all occurrencies of "UNIX" with "Linux".echo -e "ABC\nabc" | sed "/abc/d"delete lines matching "abc".echo -e "1\n2\n3\n4\n5\n6\n7\n8" | sed "3,6d"delete lines from 3 to 6.

Advanced commands

cutis a command for cutting out the sections from each line of files and writing the result to standard output.cut -b 1-3,7- state.txtcut bytes (-b) from 1 to 3 and from 7 to end of the lineecho -e "A,B,C\n1.22,1.2,3\n5,6,7\n9.99999,0,0" | cut -d "," -f 1get the first column of a CSV (-dspecifies the column delimiter,-f nspecifies to pick the

findis used to find files in specified directories that meet certain conditions. For example:find . -type d -name "*lib*"find all directories (not files) starting from the current one (.) whose name contain "lib".locateis less powerful thanfindbut much faster since it relies on a database that is updated on a daily base or manually using the commandupdatedb. For example:locate -i foofinds all files or directories whose name containsfooignoring case.

Quotes

Double quotes may be used to identify a string where the variables are interpreted. Single quotes identify a string where variables are not interpreted. Check the output of the following commands

a=yes

echo "$a"

echo '$a'

The output of a command can be converted into a string and assigned to a variable for later reuse:

list=`ls -l` # Or, equivalently:

list=$(ls -l)

Processes

- Run a command in background:

./my_command & Ctrl-Zsuspends the current subprocess.jobslists all subprocesses running in the background in the terminal.bg %nreactivates thefg %nbrings theCtrl-Cterminates the subprocess in the foreground (when not trapped).kill pidsends termination signal to the subprocess with idpid. You can get a list of the most computationally expensive processes withtopand a complete list withps aux(usuallyps auxis filtered through a pipe withgrep)

All subprocesses in the background of the terminal are terminated when the terminal is closed (unless launched with nohup, but that is another story...)

How to get help

Most commands provide a -h or --help flag to print a short help information:

find -h

man command prints the documentation manual for command.

There is also an info facility that sometimes provides more information: info command.

Introduction to git

Version control

Version control, also known as source control, is the practice of tracking and managing changes to software code. Version control systems are software tools that help software teams manage changes to source code over time.

git is a free and open-source version control system, originally created by Linus Torvalds in 2005. Unlike older centralized version control systems such as SVN and CVS, Git is distributed: every developer has the full history of their code repository locally. This makes the initial clone of the repository slower, but subsequent operations dramatically faster.

How does git work?

- Create (or find) a repository with a git hosting tool (an online platform that hosts you project, like GitHub or Gitlab).

git clone(download) the repository.git adda file to your local repo.git commit(save) the changes, this is a local action, the remote repository (the one in the cloud) is still unchanged.git pushyour changes, this action synchronizes your version with the one in the hosting platform.

How does git works? (Collaborative)

If you and your teammates work on different files the workflow is the same as before, you just have to remember to pull the changes that your colleagues made.

If you have to work on the same files, the best practice is to create a new branch, which is a particular version of the code that branches form the main one. After you have finished working on your feature you merge the branch into the main.

Other useful git commands

git diffshows the differences between your code and the last commit.git statuslists the status of all the files (e.g. which files have been changed, which are new, which are deleted and which have been added).git logshows the history of commits.git checkoutswitches to a specific commit or brach.git stashtemporarily hides all the modified tracked files.

An excellent visual cheatsheet can be found here.

SSH authentication

- Sign up for a GitHub account.

- Create a SSH key.

- Add it to your account.

- Configure your machine:

git config --global user.name "Name Surname"

git config --global user.email "name.surname@email.com"

See here for more details on SSH authentication.

The course repository

Clone the course repository:

git clone git@github.com:pcafrica/hpc_for_data_science_2023-2024.git

Before every lecture, download the latest updates by running:

git pull origin main

from inside the cloned folder.

Exercises

Exercise 1: basic Bash commands

Perform the following tasks in your command-line terminal.

- Navigate to your home folder.

- Create a folder named

test1. - Navigate to

test1and create a new directorytest2. - Navigate to

test2and go up one directory. - Create the following files:

f1.txt,f2.txt,f3.dat,f4.md,README.md,.hidden. - List all files (including hidden ones).

- List only

.txtfiles. - Move

README.mdto foldertest2. - Move all

.txtfiles totest2in one command. - Remove

f3.dat. - Remove all contents of

test1and the folder itself in one command.

Exercise 2: dataset exploration

You can access an open dataset of logs collected from a high-performance computing cluster at the Los Alamos National Laboratories. The dataset is available on this webpage.

To download the dataset using wget, run the following command:

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/logpai/loghub/master/HPC/HPC_2k.log_structured.csv

After downloading the dataset, perform the following analyses using only Bash commands.

- Find out how many unique node names are present in the dataset.

- Export the list from the previous point to a file named

nodes.log - Determine the number of times the "unavailable" event (E13) has been reported.

- Identify the number of unique nodes that have reported either event E32 or event E33.

- Calculate how many times the node "gige7" has reported a critical event (E15).

- Find out how many times the "node-2" node has been reported in the logs.

Exercise 3: creating a backup script

In this exercise, you'll create a Bash script that automates the process of creating a backup of a specified directory. The script should accomplish the following tasks:

- Receive the directory to backup as an input argument.

- Create a timestamped backup folder inside a specified backup directory.

- Copy all files and directories from the user-specified directory to the backup folder.

- Compress the backup folder into a single archive file.

Note: You can use basic commands like read, mkdir, cp, tar, and echo.

Hint: Generate a timestamp in the format YYYYMMDD_hhmmss with date +%Y%m%d_%H%M%S.

Exercise 3: creating a backup script. Instructions

- Create a new Bash script file named

backup.sh. - Inside the script, use basic Bash commands to implement the following steps:

- Prompt the user to enter the directory they want to back up.

- Create a timestamped backup folder (e.g.,

backup_<timestamp>) inside a specified backup directory (you can define this directory at the beginning of your script). - Copy all files and directories from the user-specified directory to the backup folder.

- Compress the backup folder into a single archive file

backup_<timestamp>.tar.gz. - Display a message indicating the successful completion of the backup process.

- Test your script by running it in your terminal. Ensure it performs all the specified tasks correctly.

- (Bonus) Implement error handling in your script. For example, check if the specified input directory exists.

Exercise 4: hands on git. Collaborative file management (1/3)

- Form groups of 2-3 members.

- Designate one member to create a new repository (visit https://github.com/ and click the

+button in the top right corner), and ensure everyone clones it. - In a sequential manner, each group member should create a file with a distinct name and push it to the online repository while the remaining members pull the changes.

- Repeat step 3, but this time, each participant should modify a different file than the ones modified by the other members of the group.

Exercise 4: hands on git. Collaborative file management (2/3)

Now, let's work on the same file, main.cpp. Each person should create a hello world main.cpp that includes a personalized greeting with your name. To prevent conflicts, follow these steps:

- Create a unique branch using the command:

git checkout -b [new_branch]. - Develop your code and push your branch to the online repository.

- Once everyone has finished their work, merge your branch into the

mainbranch using the following commands:

git checkout main

git pull origin main

git merge [new_branch]

git push origin main

Exercise 4: hands on git. Collaborative file management (3/3)

How to deal with git conflicts

The first person to complete this process will experience no issues. However, subsequent participants may encounter merge conflicts.

Git will mark the conflicting sections in the file. You'll see these sections surrounded by <<<<<<<, =======, and >>>>>>> markers.

Carefully review the conflicting sections and decide which changes to keep. Remove the conflict markers (<<<<<<<, =======, >>>>>>>) and make the necessary adjustments to the code to integrate both sets of changes correctly.

After resolving the conflict, commit your changes and push your resolution to the repository.

Warning:

Warning:

Please get your laptop and your Ulysses account ready by Wednesday!

Warning:

Warning: